The earliest motorcycles were designed chiefly to carry their riders effortlessly up a hill, but it did not take long for competitive enthusiasts to turn the mechanical climb into a genuinely high-flying sport.

By Charlie Lecach - photos : C. Lecach & Indian Motorcycle

In our great-grandfathers’ day, “Always aim further, and higher” could have been the motto of countless inventors and tinkerers in mechanics. Around the turn of the 20th century, those hard uphill climbs so dreaded by cyclists were used as a main selling point by early motorcycle manufacturers.

Many promoted their “motorized bicycles” by showing how they could climb a hill with zero effort. The first ever recorded hillclimbing event dates back to the dawn of motorcycling, when the New York Motorcycle Club organised the “impossible climb” demonstration at Riverdale Hill on 30 May 1903. The winner – riding a V-twin he had built himself – was Glenn Curtiss, who would go on to become a famous aviation pioneer. It goes without saying that the slopes these early riders had to tackle were not the same gradient as the ones faced by latter-day bikers on more technically advanced motorbikes. Over the years, those clapped-out old single-cylinders were superseded by more powerful twin-cylinders, leather drive belts were replaced by chains, and frames became sturdier than before.

Steeper hills were selected as the sport gained in popularity from 1920 onwards – largely due to the decline of the old “motordrome” racetracks, which were considered too dangerous. Unlike boardtrack racing (a real “widow-making” discipline), slant artists – as the hillclimbers came to be known – rarely injured themselves.

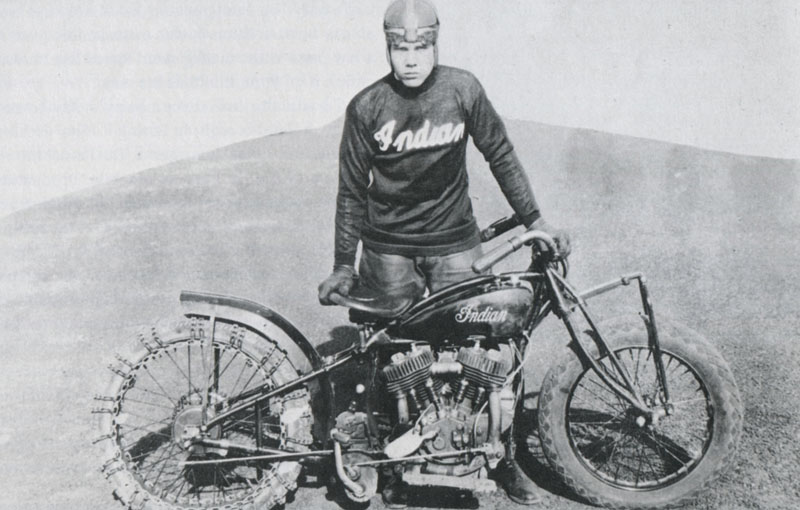

Nonetheless, it remained a spectacular sport that clearly highlighted what motorbikes could achieve. So much so that manufacturers like Indian Motorcycle invested in it heavily and promoted the sport to draw big crowds. Out in the depths of the countryside, improvised paddocks were set up and spectators gathered at the bottom of the famous climbs. The vehicles that brought them to this display would generally be lined up along the valley as far as the eye could see. Amateurs mingled with pro riders in the pits, some of them under contract to the big brands and sporting distinctive hillclimb sweaters in their company’s colours. Their bikes had been painstakingly prepared, their Flathead engines sometimes fitted with rocker arms by Indian Motorcycle's racing department and sometimes modified with OHV kits made by Albert Crocker in Los Angeles or Andy Koslow in Chicago. What’s more, they were often filled to the brim with highly explosive alcohol-based fuels.

Other competitors, often unknowns, had cobbled together their bikes using parts from production models. When the long frame Scout 101 came out, amateurs managed to house big Chief motors in these bikes and fit them with lightweight Indian Prince single-cylinder forks, making them fiendishly potent hillclimbers. For many years, the goal of hillclimbing was simply to get up the hill – to be the only one who made it to the top without turning around, and to be crowned King of the Hill. But as technology advanced, it became not uncommon to see several successful climbs in an hour. This led to a new challenge, whereby the champion was determined by a race against the clock. In the 1930s a wire began to appear, stretched across the finish line, which triggered the judges to halt the stopwatch. Hillclimbing evolved into a kind of “vertical drag race”, a typically American sport that grew increasingly specialised.

Interest in the sport dwindled over time, to such a degree that Indian Motorcycle's official stable bowed out altogether when the Second World War broke out, and had no official involvement with it post-war.

Yet many champions such as Clem Murdaugh, "Brownie" Betar and Howard Mitzel continued to record great triumphs for Indian Motorcycle's factory, which lost no time in reporting them within the pages of its publication, Indian News. Other privately-funded riders continued to hurtle around the hills of the East Coast or California right up until the 1960s, often on modified old Scouts.

But with the advent of flat track racing and then motocross, the impossible climb faded from public memory and was only kept alive by a very small circle of enthusiasts. Towards the end of the 1980s the discipline began stirring from the ashes again. Since then, the hillclimbers of old have given way to motocross bikes with extended swing arms and knobbly tyres that “plough” the soil on steep slopes.

In 2020, John “Flying” Koester helmed one of these fast and furious machines built on an Indian FTR 750 base. Covid restrictions meant he only competed in three races that season, but he still finished sixth in the national championships. He achieved the same ranking again in 2021 against fierce competitors who race on extremely specialised machines. But Indian Motorcycle has plenty more in the tank as far as this discipline is concerned, and if a day ever comes when the hillclimbing results are the same as for flat track or bagger races, an FTR could well become King of the Hill!

Leave a Reply